The Delahaye Mozart:

rediscovery of a portrait of the 16-year-old composer

Martin

Braun

April 2006, last update November 2007

Bauer and Deutsch (1963) suggested the possibility that the 1772 portrait might perhaps be the known miniature portrait (diameter 5 cm) of an anonymous sitter painted on ivory and assumed to be produced by Martin Knoller in Milan in 1773 (today Mozarteum Salzburg). This hypothesis, however, is not compatible with the following statements by Maria Anna. (1) Her portrait was executed in Salzburg, not in Milan. (2) It was executed when he was 16, not 17. (3) Her portrait was not classified as a miniature, while in the same context her 1783 pastel was explicitly classified as a miniature. We have to conclude, therefore, that the location of her 1772 portrait of her brother has apparently not been reported in the published literature for the time after 1819.

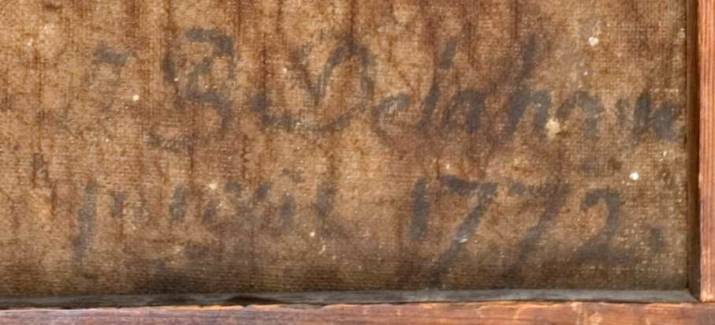

In January 2006 a portrait painting was sold at an auction that was considered as a possible candidate for a portrait of the 16-year-old W.A. Mozart (Fig. 1). The portrait, oil on canvas 53 x 38 cm, is signed on the backside of the canvas by the words "J. B. Delahaye pinxit 1772" (Fig. 2). According to the auction house Dorotheum in Salzburg, Austria, the earliest known owner of the portrait was the writer Duchess Mechtilde Christiane Maria Lichnowsky, née Countess von und zu Arco-Zinneberg, 1879-1958 (Salzburger Nachrichten, January 20, 1971). She was the great-granddaughter of Ludwig Count von Arco (1773-1854) and Maria-Leopoldine Archduchess von Österreich-Este (1776-1848). Further, she was married to Duke Karl Max Lichnowsky (1860-1928), who was the great-grandson of Duke Karl Alois Johann Nepomuk Vincenz Leonhard von Lichnowsky (1761-1814). Because both the Arco family and the Lichnowsky family had close ties to the Mozart family (Eisen and Keefe, 2006), it seems highly plausible that at some point in time after 1819 the portrait might have been acquired by one of these two families.

Next, a biometrical statistical comparison of the portrait with two known authentic adult portraits of W.A. Mozart is reported. These are the so-called Bologna Mozart, painted by an unknown painter in Austria in 1777, now in the Civico Museo Bibliografico Musicale, Bologna, Italy, and Wolfgang's portrait from the family painting of the Mozarts by Della Croce from 1780-81, now in the Internationale Stiftung Mozarteum, Salzburg, Austria. The result is that the person shown by the portrait from 1772 has to be considered as the same person as the one shown by the other two portraits, with an error probability of one in over 10,000,000.

Landmark test on non-identity

Face identification is largely determined by proportions and angles of landmark distances, such as length of nose. In these respects the new face does not differ from either of the two known faces more than these differ between themselves (Figs. 3-5). Thus, the overall landmark test on non-identity is negative, and identity of the new face with the two others remains possible.

Most faces have a number of non-general features, such as an elevation on the ridge of the nose. The comparison of such features between the two known faces and the new face shows no significant difference. Thus, also the feature test on non-identity is negative, and identity of the new face with the two others remains possible.

Digital feature test on identity

Many faces have a number of digital features. These are features that are either obviously present or obviously absent. If different portraits, for which the non-identity tests have been negative, have a sufficient number of digital features in common, the probability of subject identity can be determined statistically. The following seven digital features appear both in the new face and in the two known faces:

1) Horizontal wrinkle line halfway between mouth and tip of chin.

2) Nose tip with two tip-defining points.

3) Elevation on the ridge of the nose.

4) Horizontal indentation across the root of the nose.

5) Dark curved segments (suffused skin tissue) below the eyes.

6) Fold of upper eyelid in parallel to and displaced from edge of eyelid.

7) Thinning-out in the lateral third of the right eyebrow.

It should be noted that the three features of the nose are less strong in the new face. There are two possible reasons for this. First, at the age of 16 the face may still have been less adult-like and less masculinized than at the age of 21 and 25. Second, the painter may have reduced these features in order to make the face more handsome. It was important for portraitists not to delete unpleasant traits completely, because then they would jeopardize their reputation as skilled painters of high-fidelity portraits. But if they only reduced an unpleasant trait while keeping it just visible, they avoided this problem. Careful observation of the brightness differences reveals that all three features of the nose are fully present also in the new face.

Because the seven features are usually visible in real faces under common light conditions, their frequency in the general population could be determined by feature counts in public portrait galleries.

The frequencies of features 2, 3, 4, and 7 had been determined in an earlier study (Braun, 2005 and 2006ab) from a corpus of 103 adult Caucasian male portrait paintings, and separately from a corresponding corpus of 103 portrait photographs. The frequencies of features 1, 5, and 6 had been determined in another earlier study (Braun, 2006c) from a corpus of 60 portrait paintings, and separately from a corresponding corpus of 70 portrait photographs.

The count of feature frequencies in both databases of Braun (2006c), separately for paintings and photographs, had revealed that trait 5 and 6 appeared in the same face more often than could be expected from their single frequencies. This observation was biologically plausible, because the probability of both traits may depend on qualities of under-skin tissue that are similar above and below the eye. Therefore, the co-occurrence of these two traits in a face had to be considered as a single combined trait.

The complete results were as follows (first paintings, then photographs):

1) Horizontal wrinkle line halfway between mouth and tip of chin: 25%

& 30%.

2) Nose tip with two tip-defining points: 7% & 7%.

3) Elevation on the ridge of the nose: 5% & 1%.

4) Horizontal indentation across the root of the nose: 7% & 2%.

5 & 6) Dark curved segments below the eyes AND described fold of

upper eyelid: 8% & 9%.

7) Thinning-out in the lateral third of the right eyebrow: 2% &

2%.

Next, these six features were tested on correlations. Because all tests were negative and because there is also no biological rationale to assume any correlation, the six features have to be considered as stochastically independent. Thus, the frequency of their joint occurrence is computed by multiplication of the single frequencies. The results for the probability that two non-relatives have the six features in common are one in over 11,000,000 re the painting databases, and one in over 156,000,000 re the photo databases.

A well-known phenomenon in color perception strongly adds to the evidence that the Delahaye painting from 1772 really is the one that Wolfgang's sister Maria Anna owned and described in 1804 and 1819. Because a large part of the canvas area is filled by the intensive blue of the jacket, the perception of the color of the face is shifted towards yellow-orange, the contrast color of the blue of the jacket. This type of phenomenon is assumed to have already been known by Leonardo da Vinci, was first scientifically described by Michel Eugène Chevreul in 1839, and is today described under the term "color induction" (Zaidi, 1999). It is also well established that the extent of such a perceptional color shift varies greatly between subjects. The result is that the blue jacket gives the sitter's face an appearance of being somewhat sun-tanned, and that this impression varies greatly between observers. Maria Anna apparently was highly sensitive to this effect and then so irritated by it that she explicitly mentioned it both in 1804 and in 1819. One has to bear in mind that a sun-tanned face, while being a sign of health or even affluence in our days, was a sign of a low social status 200 years ago. It was the hallmark of toiling in the fields. Interestingly, Maria Anna found two completely different reasons, at the two instances, when trying to explain the irritating color of her brother's face. In 1804 she wrote: "…. painted as he came back from Italy, being fully in Italian tan." Fifteen years later she wrote: "…. because he had suffered a grave illness, the image looks sickly and very yellow." (Bauer and Deutsch, 1963). By finding excuses for her brother's apparent face color, "Nannerl" unknowingly and most charmingly delivered a seal for the authenticity of her treasure, for us, 200 years later.

Update November 2007

A new investigation of the posthumous portrait by Barbara Krafft revealed

that she painted one significant facial trait that does not exist

in the main model portrait that she used, the one by Della Croce (see

above). This trait is a vertical indentation in the middle of the

lower part of the chin. Click here.

This trait gives the chin the appearance of two hemispheres. It has

a frequency of 49 % in the above-mentioned database of 103 portrait

paintings. Because this trait is generally concealed in profile portraits

and could therefore not be present in Nannerl's miniature profile-portrait

of her brother (see above), Barbara Krafft either invented it or saw

it in the third of Nannerl's model portraits, the one of the 16-year-old

Wolfgang. As the comparison shows, this trait is absolutely identical

in the Delahaye (1772) and in the Krafft (1819). Krafft had a reputation

of being a highly naturalistic portraitist. So it is extremely unlikely

that she simply made up this trait. It is very probable, however, that

she had noticed that the chin in the Della Croce is poorly painted and

shows a rather unrealistic asymmetry of the chin bulge. In such a situation

it must have been logical for Krafft to consult the only other model

that was available and could be of use: the portrait of the 16-year-old

Wolfgang. As can be seen in Fig. 3, the trait is also present in the

Bologna Mozart: But this painting was not available to Krafft. In conclusion,

the chin in the famous Krafft Mozart presents further strong evidence

that the newly rediscovered Delahaye (1772) is identical with Nannerl's

portrait of her brother as a 16-year-old.

Bauer, Wilhelm A., and Deutsch, Otto Erich (1963) Mozart, Briefe und Aufzeichnugen. Gesamtausgabe, herausgegeben von der Internationalen Stiftung Mozarteum Salzburg, gesammelt und erläutert von Bärenreiter Verlag, Kassel/Germany, letters 1364 and 1391 including related commentaries.

Braun, Martin (2005) The last portrait of W.A. Mozart: A biometrical statistical comparison. Internet publication (search title), April 2005 (Republished on demand in: Mozart-Jahrbuch 2005 des Zentralinstitutes für Mozartforschung der Internationalen Stiftung Mozarteum Salzburg, Austria, 2006, pp. 253-255.).

Braun, Martin (2006a) Das letzte Portrait von Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Ein biometrisch-statistischer Vergleich. In: Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Ed.), Das Mozartportrait in der Berliner Gemäldegalerie. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, pp.19-22.

Braun, Martin (2006b) Das letzte Portrait von Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Ein biometrisch-statistischer Vergleich. In: Keller, P., Kircher, A. (Eds.), Zwischen Himmel und Erde - Mozarts geistliche Musik: Katalog mit CD, 256 Seiten. Verlag Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg, pp. 75-76.

Braun, Martin (2006c) Identification of a portrait of W.A. Mozart from the mid-1780s: A biometrical statistical comparison with the five known authentic adult portraits. Internet publication (search title), January 2006, and in press.

Eisen, Cliff, and Keefe, Simon P. (Eds.) (2006) The Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia. Cambridge University Press.

Eveillard, James (2000) Vincent Corbel 1792. In: Patrimoine des Communes du Morbihan. Editions Flohic, p. 108.

Salzburger Nachrichten, January 20, 1971.

Zaidi, Qasim (1999) Color and brightness induction: From Mach bands to 3-D configurations. In: Color Vision: From Genes to Perception. Gegenfurtner, K.R. and Sharpe, L.T. (Eds.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 317-344.

Acknowledgements

I thank Dan Leeson for his valuable support in the document search concerning Maria Anna's possession of portraits of her brother Wolfgang.