The earliest portrait of W.A. Mozart -

A biometrical statistical analysis of the newly discovered Fruhstorfer Mozart from c1762

Martin Braun - August 2013

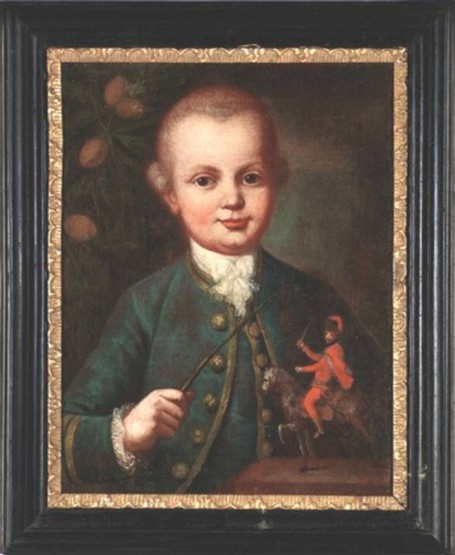

The painting is in oil on canvas, 49 x 37 cm, apparently still with its first frame, 62 x 50 cm. The portrait was sold in 2010 from a private home about 70 km from Salzburg in Austria, where it had been from 1922. Before that year the portrait was owned by the Austrian brewer family Fruhstorfer. The earlier provenance is not known. It is known, however, that in 1850 Rosina Fruhstorfer and her husband Siegmund Hoffmann became the owners of the pub Bergerbräu in the Linzergasse in Salzburg. This traditional Salzburg pub, which is documented from 1413, was in the neighborhood of W.A. Mozart's home. In 1777 W.A. Mozart was invited to the wedding of the brewer of the Bergerbräu.

1) Photographs of the painting (Figs. 1-4)

2) The status of scientific identification of faces in paintings

3) The three Mozart portraits used for comparison

4) Biometrical statistical analysis

5) Reference images (Figs. 5-10)

6) Where was it painted?

7) Literature

8) The author

9) Update January 2016

1) Photographs of the painting (Figs. 1-4)

Fig. 1 The painting "The Fruhstorfer Mozart" without frame, 49 x 37 cm.

Fig. 2 The painting "The Fruhstorfer Mozart", head and shoulders.

Fig. 3 The painting "The Fruhstorfer Mozart", lower part.

Fig. 4 The painting "The Fruhstorfer Mozart", hand.

Scientific identification of faces in old paintings is still a young discipline. Until a few years ago one could even hear the opinion that the whole discipline was a false beginning. In arts we would be dealing with artifacts, not with images that mirror reality such as in photography. This view, however, is based on a serious category error. From the age of the Renaissance until the beginning of the age of photography, portrait painters worked under a condition of strictly limited freedom. They were commissioned to produce a facial image that would generally be recognized as faithful by anybody who had seen the depicted person. Only in a few exceptional cases could facial traits be arbitrarily altered. As a rule, they had to be reality-bound.

Due to the increasing importance of forensic face identification from

digital photos, and due to the success of scientific face identification

in much discussed cases of Shakespeare portraits and Mozart

portraits, opinions have changed dramatically in recent years. Today

researchers are funded even for the exploration of possible merits of

software-based face identification in arts (1, 2).

3) The three Mozart portraits used for comparison

The Mozart portrait that would be the historically closest one is the

so-called Lorenzoni Mozart (Fig. 5). It was commissioned

by the father, Leopold Mozart, and is today attributed to the year 1763

and the painter Pietro Antonio Lorenzoni. However, it had to be excluded

as a reference portrait for the present study due to grave painting errors.

In 2006 a newly discovered boy portrait was found to be a partly altered

copy of the Lorenzoni Mozart (3). At that time an investigation

of the case had revealed the following painting errors in the Lorenzoni

Mozart:

Quoted from the paper of 2006 (3):

"A close inspection of the Lorenzoni Mozart reveals that the painter

made several technical mistakes that a skillful portrait painter would

not make. First, the general impression is that we are dealing with a

face that is adult-like. In particular, the proportions of the forehead

and of the chin are typical for adults, but untypical for a child aged

seven. If these parts are cut off, the face suddenly becomes child-like.

Another serious construction error lies in the treatment of the perspective.

The frontal plane of the head looks pressed-in at its right side, because

the right-side plane of the head is given too much space on the canvas.

The horizontal distance between right eye and right ear is much too long.

Besides the two global errors there are also five major errors

in face details:

1) The right side of the nose is considerably higher than its left side.

Such an asymmetry never occurs in a healthy nose, and it does not occur

in other Mozart portraits.

2) The lower part of the nose is bent toward the right. Also this asymmetry

never occurs in a healthy nose, and it does not occur in other Mozart

portraits.

3) The shadow on the left side of the nose is wrong in four respects:

a) too dark, b) too sharp at its edges, c) too high up along the nose,

d) straight line cuts across nose tip, instead of circling around it.

4) The left eye is focused on the observer, but the right eye is slightly

turned lateral. This condition does not occur in other Mozart portraits.

5) The lower part of the right ear is highly unnatural and fully incompatible

with other Mozart portraits."

Therefore, instead of the Lorenzoni, the chronologically next Mozart portrait

that is universally regarded as authentic was used. It is the portrait

painted by Saverio dalla Rosa in 1770. For additional comparisons

also two portraits of the adult Mozart were used. These are the so-called

Bologna Mozart from 1777, which is universally regarded as authentic,

and the so-called Edlinger Mozart from 1790, which is today widely

regarded as authentic both by the general public and by art historians

in Berlin (4) and in Vienna (5).

4) Biometrical statistical analysis

A. Landmark test on non-identity

Face identification is largely determined by proportions and angles of

landmark distances, such as length of nose. In the present case, one has

to take into account that facial proportions in a six-year-old deviate

sharply from those in a fourteen-years-old or in an adult. In the child,

forehead and eyes are proportionally larger, whereas nose and chin are

proportionally smaller (Fig. 6). Further, it must be

taken into account that in the dalla Rosa the top of the forehead is covered

by a wig. Considering these circumstances, the new face does not reveal

one significant landmark deviation from either of the two reference faces

in Fig. 6. Thus, the landmark test on non-identity is

negative, and identity of the subjects remains possible.

B. Feature test on non-identity

Most faces have a number of non-general features, such as a vertical indentation

in the middle of the lower part of the chin. Comparison of such features

between the Fruhstorfer and the dalla Rosa shows three differences. In

the dalla Rosa the hanging cheeks with a skin fold under the chin (trait

1 in Figs. 7 and 10) are absent,

possibly concealed by clothing. In the Fruhstorfer the elevation on the

ridge of the nose and the horizontal indentation across the root of the

nose (see Figs. 8-10) are absent.

Because each of the three differences can be accounted for by the difference

in age, also the feature test on non-identity is negative, and identity

of the subjects still remains possible.

Excursus: Comment on the eye colors of W.A. Mozart

Heterochromia iridum is a condition where either the two eyes differ in

color of the iris (complete heterochromia) or the color varies within

an iris (sectoral heterochromia). From the large number of portraits of

W.A. Mozart that we have today we can conclude that his eyes almost certainly

had sectoral heterochromia. Each of the five portraits presented in this

study clearly shows this condition (enlarge images up to 200 %, if necessary).

Lorenzoni (Fig. 5): right eye, gray-blue - left eye,

gray-blue plus light-brown.

Fruhstorfer (Fig. 7): right eye, brown (upper part)

plus gray (lower part) - left eye, brown (more centrally) plus gray (more

peripherally).

Dalla Rosa (Fig. 8): right eye, gray - left eye, gray

plus brown.

Bologna (Fig. 9): right eye, brown plus light-brown

(or gray) - left eye, brown plus gray.

Edlinger (Fig. 10): right eye, light-gray-brown (centrally)

plus gray (peripherally) - left eye, light-gray (centrally) plus gray

(peripherally).

Additionally, it should be noted that in art history the eye colors in

old portrait paintings are considered as notoriously unreliable for the

following reasons.

- Both pigment layers and varnish can change chemically and physically

with age resulting in color alterations.

- Dependence on illumination of the painted person.

- Dependence on curiosity of the artist to examine the eye colors closely.

- Dependence on illumination of the finished painting.

In conclusion, portraits of W.A. Mozart typically show multi-colored eyes,

which would be consistent with the condition of sectoral heterochromia

iridum. Differences in apparent eye-color combinations across Mozart portraits

can easily be accounted for by circumstantial conditions.

C. Digital feature test on identity

Many faces have a number of digital features. These are features that

are either obviously present or obviously absent. If two portraits, for

which the non-identity tests have been negative, have a sufficient number

of digital features in common, the probability of subject identity can

be determined statistically. The following eight digital features appear

in the Fruhstorfer and at least one of the reference portraits (Figs.

7-10):

1) Hanging cheeks with a skin fold under the chin.

2) Vertical indentation in the middle of the lower part of the chin.

3) Horizontal wrinkle line between mouth and tip of chin.

4) A nose tip with two tip-defining points.

5) Dark half-circles (suffused skin tissue) below the eyes.

6) Left eye more widely opened than right eye.

7) Fold of upper eyelid in parallel to and displaced from edge of eyelid.

8) Thinning-out in the lateral third of the right eyebrow.

Excursus: Comment on feature 6

The occurrence of this trait in a painted portrait is a fortunate one,

because it provides additional evidence. The trait is not very rare, but

painters tended to neglect it. In photos it had a prevalence of 9 %, but

in paintings one of only 5 % (see below). The human brain is extremely

sensitive in noting slight changes in the distance between lower and upper

eyelid, because such changes are essential elements in emotional expression.

For this reason, size differences between the two eyes of a portrait are

easily detected. If artists wanted to do an extra favor to a customer

with such a condition, they could give it a special treatment. In our

case, the left eye is measurably more widely opened in the Fruhstorfer

(Fig. 7) and in the dalla Rosa (Fig. 8).

Interestingly, in the Bologna (Fig. 9) and in the Edlinger

(Fig. 10) there is no measurable difference but an

apparent one. In both paintings the artists made the left eye appear bigger

by skillful manipulation of local brightness. The painter of the Bologna

over-emphasized the brightness of the edge of the left eye's lower lid,

whereas Edlinger made the right eye appear smaller by over-emphasizing

the shadow below the upper lid and by adding extra brightness to the reflection

zones above and below the left eye. Tricks of this type protected artists

against possible accusations of unfaithfulness on the one hand, and disrespectful

realism on the other hand. If asked, they could reply: "The left

eye looks bigger to me," in the first case, or "Both eyes are

of the same size - you can measure them," in the second case.

Because the eight features are visible in almost all common light conditions of portrait painting, their frequency in the general population could be determined by feature counts in public portrait galleries.

A corpus of 132 adult Caucasian male portrait paintings was established by extracting naturalistic style portraits that were available in sufficient resolution from the internet archives of the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, the National Gallery of Arts in Washington D.C., the National Gallery in London, and the Musée du Louvre in Paris.

A corresponding corpus of 108 portrait photographs was established by extracting, in order of listing, the results from Google picture searches that included the search term "portrait".

The count of feature frequencies, separately for paintings and photographs, revealed that in both databases trait 1 and 3 appeared in the same face more often than could be expected from their single frequencies. This observation is biologically plausible, because the probability of both traits is likely to increase with the amount of under-skin tissue in the lower jaw. Therefore, the co-occurrence of these two traits in a face had to be considered as a single new trait.

Similarly, the count of feature frequencies, separately for paintings and photographs, also revealed that in both databases trait 5 and 7 appeared in the same face more often than could be expected from their single frequencies. Also this observation is biologically plausible, because the probability of both traits may depend on qualities of under-skin tissue that are similar above and below the eye. Again, the co-occurrence of these two traits in a face had to be considered as a single new trait.

The feature frequencies were as follows:

1 and 3) Hanging cheeks with a skin fold under the chin AND horizontal wrinkle line between mouth and tip of chin: 8 % in paintings, 6 % in photographs.

2) Vertical indentation in the middle of the lower part of the chin: 46 % in paintings, 31 % in photographs.

4) A nose tip with two tip-defining points: 7 % in paintings, 7 % in photographs.

5 and 7) Dark half-circles (suffused skin tissue) below the eyes AND fold of upper eyelid in parallel to and displaced from edge of eyelid: 8 % in paintings, 9 % in photographs.

6) Left eye more widely opened than right eye: 5 % in paintings, 9 % in photographs.

8) Thinning-out in the lateral third of the right eyebrow: 2 % in paintings, 2 % in photographs.

Next, these six features or feature combinations were tested on correlations. Because all tests were negative and because there is also no biological rationale to assume any correlation, the six features have to be considered as stochastically independent. Thus, the frequency of their joint occurrence is computed by multiplication of the single frequencies. The results for the probability that two non-relatives have the six features in common are one in over 4,800,000 re the painting database, and one in over 4,700,000 re the photo database.

Further, it should be noted that the probability estimate would have

been even stronger, if non-digital features such as the shape of the corners

of the mouth had entered the calculation.

5) Reference images (Figs. 5-10)

Fig. 5 Five major painting errors in face details of the Lorenzoni Mozart (see sect. 3).

Fig. 6 Global comparisons with the dalla Rosa (1770) and the Edlinger (1790).

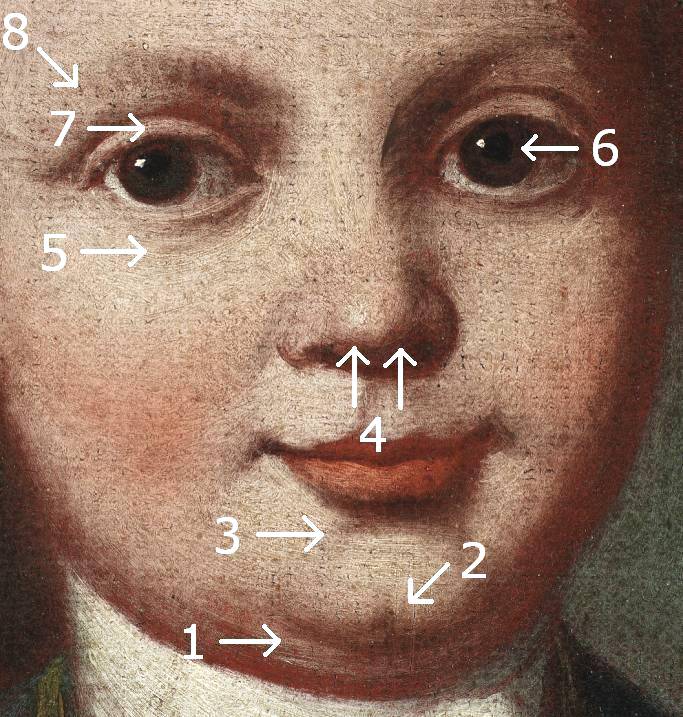

Fig. 7 The facial traits used in the present study in the Fruhstorfer Mozart (c1762).

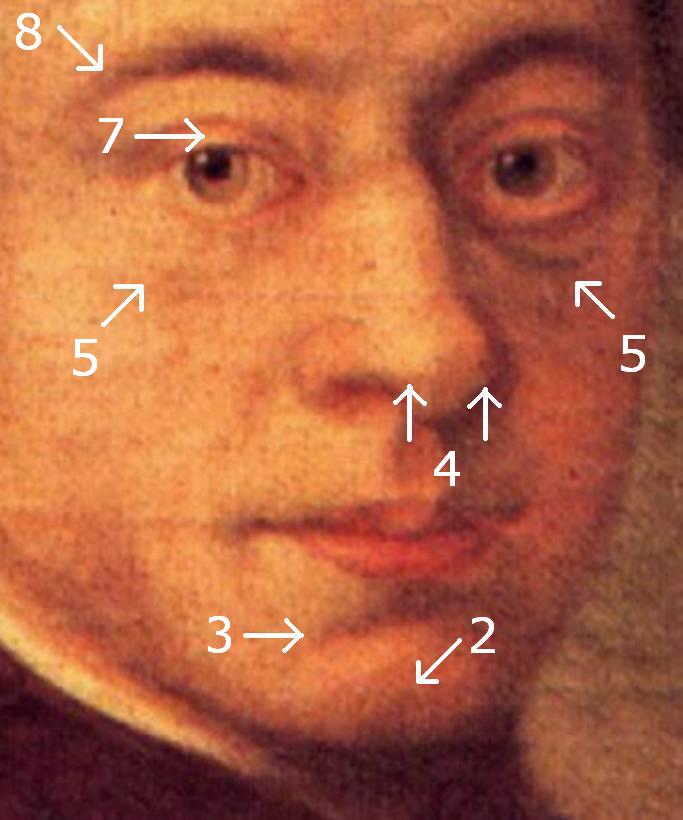

Fig. 8 The facial traits used in the present study in the dalla Rosa Mozart (1770).

Fig. 9 The facial traits used in the present study in the Bologna Mozart (1777).

Fig. 10 The facial traits used in the present study in the Edlinger Mozart (1790).

Inspection of the artist's brushwork revealed a fast but very skillful hand. This indicates a competence and experience that was more likely to be found in Munich or in Vienna than in Salzburg. In 1762 W.A. Mozart was for the first time presented as a miracle boy to the high nobility in Munich and in Vienna. At that time he was six years old, which would be consistent with the apparent age of the boy on the painting. Further, also the likelihood to find the depicted expensive clothing for a little boy and a sponsor for a high-quality portrait was clearly greater in Munich or in Vienna than in Salzburg.

(1) Miller B. Research on Application of Face-recognition Software to Portrait Art Shows Promise. In: UCR Today 2013-05-31, University of California, Riverside. Online publication.

(2) Art research effort aided by face recognition. In: BBC News 2013-06-06. Online publication.

(3) Braun M. Identification of a secondary portrait of W.A. Mozart as a boy: A biometrical statistical comparison with the authentic boy portrait from 1763 attributed to Lorenzoni. In: DN Leeson. The Mozart Cache: The Discovery and Examination of a Previously Unknown Collection of Mozartiana. AuthorHouse, Bloomington, Ind., USA, 2008, pp 216-221. (ISBN 978-1-4343-8415-7)

(4) Michaelis R. Das Mozartporträt in der Berliner Gemäldegalerie. Mit Beiträgen von Martin Braun und Ute Stehr. Berlin: Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (2006).

(5) Grabner S, Krapf M (Eds), Aufgeklärt Bürgerlich - Porträts von Gainsborough bis Waldmüller 1750-1840, Hirmer Verlag, München 2006.

Martin Braun is a neurobiologist and a composer. He is specialized on

investigating music related auditory physiology. Since 1993 he has published

original research on inner ear function, otoacoustic emissions, pitch

processing in the auditory midbrain, neurophysiology of acoustical sensory

consonance, precognitive absolute pitch, and the physiology of octave

circularity of pitch. From 2000 he works for the independent research

organization Neuroscience of Music near Karlstad in Sweden.

During the years 2005 and 2006 he carried out biometrical statistical

analyses of several portrait paintings of W.A. Mozart, whose authenticity

had been a matter of long-standing controversies. In the case of four

portraits he found compelling evidence that they had to be regarded as

authentic. These are the Edlinger Mozart (1790), the Hickel Mozart (c1785),

the Delahaye Mozart (1772), and the Greuze Mozart (1763-64). Publication

of the results caused further archival research elsewhere. In all cases,

new archival findings since then have confirmed Braun's results, and the

four portraits are today widely accepted as authentic.

Listing of author's

publications

9) Update January 2016

In 2014 the painting was attributed to the Italian painter Gennaro Basile (1722-1782) on multiple stylistic grounds by Barbara Kaiser, director of Schloss Eggenberg and Alte Galerie (Joanneum Graz, Austria). The art historian had special expertise on the portraits by Basile, because she had closely examined a collection of 58 portraits of the nobility of Styria / Austria by this artist (written personal communication, 2014).

A technical analysis of the painting's color pigments in 2014 by Manfred Schreiner, professor and engineer at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna / Austria confirmed that the same pigments were used as in an established comparison painting by Basile.