The Greuze Mozart - rediscovery of a portrait painting

Contents

B. Identification of Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725-1805) as the painter

C. Identification of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1891) as the sitter

D. Overburdened children in the work of Greuze

Description:

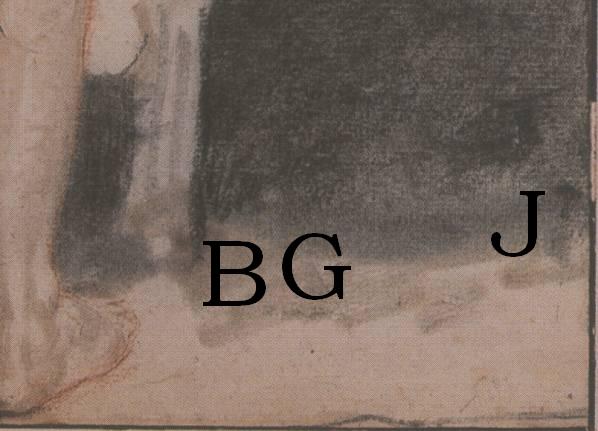

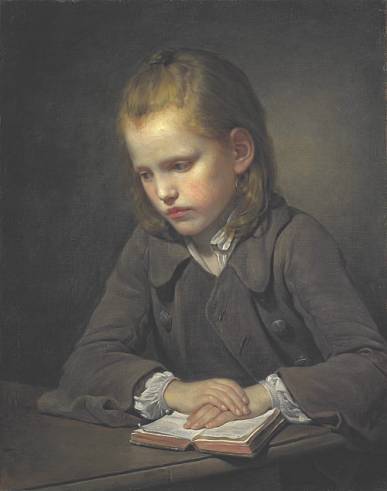

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, painted by Jean-Baptiste Greuze 1763-64 in

Paris. Oil on canvas, 34 x 45 cm. Signed at middle right, on proper

left shoulder: "BJG". New Haven, Connecticut, USA, Yale University

Collection of Musical Instruments (Figs. 1a, 1b).

Provenance:

A.S. Rambo, art dealer in Paris, offered for sale as part of a private

collection of 30 paintings in 1910.

Belle Skinner, Holyoke, Massachusetts, USA, acquired in Paris during

summer 1911.

Yale University Collection of Musical Instruments acquired 1960.

Exhibitions:

Mozart Museum, Salzburg, Austria, July 23 to October 28, 1910, in connection

with the Mozart Festival. 4326 visitors. Reported in many Austrian and

German newspapers and journals, during and after the exhibition, and

generally praised as a sensational discovery.

Bibliography:

William Skinner, The Belle Skinner Collection of Old Musical Instruments

at Holyoke, Massachusetts. Springfield, Massachusetts, USA, 1933. Catalogue

No. 24: "Portrait of Mozart", pp. 72-74.

B. Identification of Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725-1805) as the painter

As late as January 2006 neither the center of documentation at the Louvre in Paris nor the Greuze Museum in Tournus, France, had any information about the data listed above. The two most obvious reasons are as follows.

First, the only general catalogue of the work of Greuze, the "Catalogue raisonné" by J. Martin and C. Masson, appeared 1906, i.e. four years before the painting appeared in the public, for the first time ever, in 1910.

Second, art historians usually do not read catalogues of museums of musical instruments.

A less obvious, but possibly decisive, reason for the unawareness of the art world concerning the painting may lie in the fact that the catalogue of 1933 does not mention that the painting was signed by the painter. Further, the color photo that was included in the catalogue does not have a sufficient resolution to reveal the signature, which is rather inconspicuous. Because Greuze is well known among art experts as an outstanding painter of the 18th century, information about the signature in the 1933 catalogue would have had a good chance to reach the art world during the past 73 years. This would most probably have led to further and more thorough publications of the painting.

The peculiar softness of the signature deserves special attention. It is therefore documented in detail. Generally, if Greuze signed his work at all, he preferred inconspicuous signatures with widely varying combinations of words, initials, and letter types. An example of an almost obscure, but generally accepted, signature is found on the chalk drawing "A woman going to bed", presumably ca 1767, 37 x 58 cm, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon, France. As shown in Fig. 2, the signature was written with black chalk into a background of black chalk, even though there was plenty of free space for a clearly visible signature. Additionally, the initials are not in proper order and extremely unevenly spaced.

It should also be noted that a forger hardly would chose an idiosyncratic

and exceptional signature as we have in this case. Considering further

that there are no known reasons to question Greuze as the painter, and

considering that the painting fully conforms to style and topics of the

artist's other work, the identification of the painter of this portrait

must be regarded as complete.

C. Identification of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1891) as the sitter

When the art dealer A.S. Rambo in Paris offered the painting for sale in 1910, he stated that it was a portrait of W.A. Mozart. Further, it was in an oval frame that had a large cartouche with the letter "M" at its upper end and a plaque with the word "Greuze" at its lower end. However, according to the documents associated with the Salzburg exhibition of 1910, Rambo did not present any documentation that could prove that the sitter was Mozart. Possibly for this reason, Deutsch (1961) classified the painting as an "unauthenticated" portrait, even though he published it in a version with the frame as described above.

During the 1760s Greuze was the most celebrated painter in Paris (Barker, 1997 and 2005), and just in 1763 Denis Diderot (1713-1784) reported that Greuze was "constantly on the lookout in the streets, in churches, in markets, at the theater, on promenades, in public gatherings" to find suitable heads for his art. It is therefore likely that he met Mozart, when his family stayed in Paris between November 1763 and April 1764. The probability of an encounter was further increased by the fact that Friedrich Melchior, Baron von Grimm (1723-1807), the Mozart family's best friend in Paris and their most effective publicist there, was also a close friend and admirer of Greuze.

Still, all these circumstances cannot fully exclude the possibility that an intelligent forger falsely attributed Mozart to a random, but up till then unknown, boy portrait by Greuze. Due to the high quality of the painting, however, it is possible to resolve this question by biometrical analysis of the facial data. Because all other known portraits of Mozart as a boy are so poorly painted that it is impossible to estimate which of their facial data are reliable, the two well-known authentic portraits of Mozart as a young man were used for comparison. These are the Bologna Mozart from 1777, showing the composer at the age of 21, and the Della Croce Mozart from 1780-81, showing him at the age of 25. Both portraits have the further advantage that they present the face from a similar viewing angle as the Greuze portrait.

Figs. 4 and 5 show the facial comparisons. First, it can be observed

that there are no decisive differences in proportions and facial traits.

Minor differences that do occur can easily be accounted for by the age

differences. It should be noted though that the irises of the eyes are

slightly darker than in the adult portraits. The Bologna, the Della Croce,

and the Edlinger portrait unanimously show an iris color that has shades

of gray and hazel. The Greuze portrait shows an Iris color of dark hazel.

This minor difference may have been due to the production of the painting

after a drawing that Greuze had taken from a live sitting. A healthy child

of eight cannot sit without moving until a painted portrait is finished.

Second, the boy portrait reveals five facial traits that have earlier

been reported for the adult portraits (Braun, 2005a and 2005b).

They are listed including their frequency in the general population (first

re paintings, second re photographs):

1) Nose tip with two tip-defining points: 7 % & 7 %.

2) Elevation on the ridge of the nose: 5 % & 1 %.

3 & 4) Biologically linked traits: Dark half-circles (suffused skin

tissue) below the eyes AND fold of upper eyelid in parallel to and displaced

from edge of eyelid: 8 % & 9 %.

5) Thinning-out in the lateral third of the right eyebrow: 2 % & 2

%.

Finally, because the Mozart family visited Paris a second time, in 1766, the apparent age of the boy on the portrait was determined. A professional, who had worked with children aged 6 to 11 for 30 years on a daily basis, estimated the apparent age as 7 to 8 and considered an age of 10 as good as impossible. Mozart reached the age of 8 in January 1764. The apparent age thus indicates that Greuze painted this portrait during Mozart's first Paris visit in 1763-64.

D. Overburdened children in the work of Greuze

Children that are not altogether happy under the work that adults have scheduled for them are prominent in the work of Greuze (Fig. 6). The way Greuze placed the head of Wolfgang, low on the neck, slightly sagging forward, and inclined to the left, he clearly depicted physical tiredness. Further, by putting the left side of the face into a fairly strong shadow, the artist added an unmistakable shade of apprehension to this alert and charming face. With his portrait of Mozart, Greuze (Fig. 7) once again gave evidence not only of his extraordinary skills as a painter but also of his deep sensitivity for the human condition.

a) Greuze, A boy asleep over his book, 1755, oil on canvas, 65 x 54.5 cm, Montpellier, France, Musée Fabre.

b) Greuze, A boy with a lesson-book, 1757, oil on canvas, 62.5 x 49 cm, Edinburgh, National Gallery of Scotland.

c) Greuze, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 1763-64, oil on canvas, 34 x 45 cm, New Haven, Connecticut, USA, Yale University Collection of Musical Instruments.

d) Greuze, Young knitter asleep, 1759, oil on canvas, 68 x 58 cm, San Marino, California, USA, Huntington Library, Art Collections.

Emma Barker, Painting and Reform in Eighteenth-Century Franc: Greuze's L'Accordée de Village. The Oxford Art Journal 20, 1997, 42-52.

Emma Barker, Greuze and the Painting of Sentiment, Cambridge University Press 2005.

Martin Braun, The last portrait of W.A. Mozart: A biometrical statistical comparison. Web publication 2005a. (Republished on demand in print three times, e.g., in: Mozart-Jahrbuch 2005 des Zentralinstitutes für Mozartforschung der Internationalen Stiftung Mozarteum Salzburg/Austria, 2006, 253-255.)

Martin Braun, A new portrait of W.A. Mozart from the mid-1780s: A biometrical statistical identification. Web publication 2005b. (Printed version in press)

Otto Erich Deutsch, Mozart und seine Welt in zeitgenössischen Bildern. Bärenreiter Verlag Kassel, Basel, London, New York, 1961. Image No. 612, p. 288 and p. 370.

Denis Diderot, Salons (1759-81). Ed: J. Adhémar and J. Seznec, 4 vols. Oxford 1957- 67, rev. 1983. Vol 1, p. 236.

Jean Martin and Charles Masson, Catalogue raisonné de l'oeuvre peint et dessiné de J.-B. Greuze, suivi de la liste des gravures exécutées d'après ses ouvrages. In : Camille Mauclair, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, H. Piazza, Paris 1906.

Acknowledgements

I thank Dan Leeson for his support during the search of the painting and

Susan Thompson at Yale University for her general co-operation and technical

help.